When Statistics Tell Different Stories: The Remarkable Rain Event in Northern Israel

On November 19, 2024, the coastal region of northern Israel experienced an extraordinary rainfall event that shattered records and challenged our understanding of rainfall statistics. As a hydrologist, I found this event particularly fascinating, not just for its intensity, but for what it reveals about how we interpret and use rainfall data for infrastructure design.

The Record-Breaking Event

The event most extreme rainfall occurred in a narrow strip between Magan Michael and Ramat Hanadiv, where the meteorological station in Nachal Taninim recorded a staggering 196mm in just four hours - that’s nearly 50mm per hour sustained over four hours, To put this in perspective, this amount of rainfall would normally be expected over several weeks during the rainy season.

The Urban Impact: Zichron Yaakov

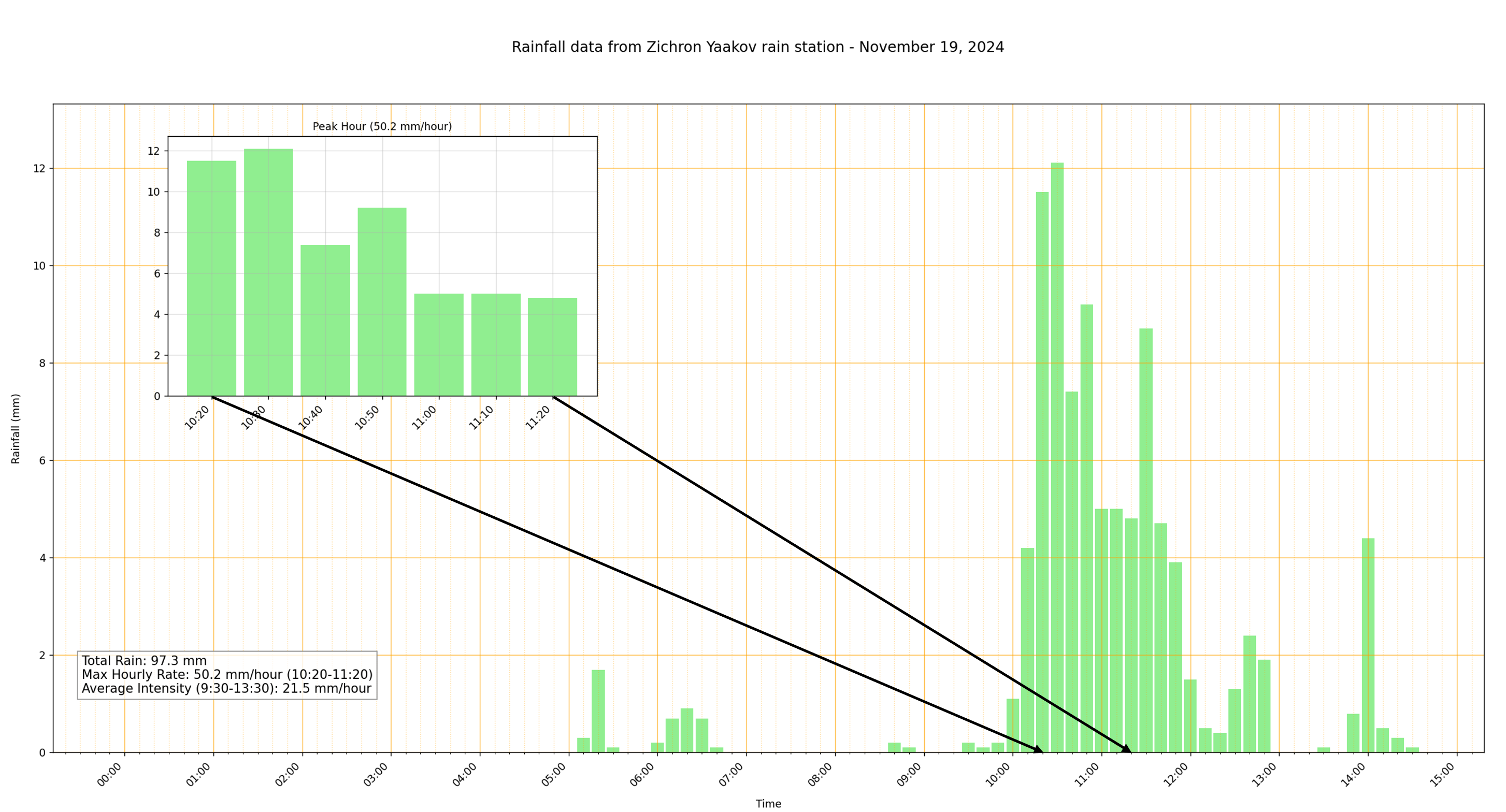

While Zichron Yaakov, the largest urban center in the affected region, didn’t experience the most extreme rainfall, its infrastructure and population density made it particularly vulnerable to the storm’s impacts. The city’s rain station recorded 97.3mm over the four-hour event, with a peak intensity of 50.2mm/hour between 10:20-11:20, and an average intensity of 21.5mm/hour. This distinction is crucial - while other areas received more rainfall, the impact on Zichron Yaakov’s urban infrastructure and larger population made it a focal point for analysis and future planning. The intense rainfall overwhelmed the city’s drainage systems, leading to significant urban flooding. Streets turned into rushing streams, and numerous residential areas experienced severe flooding. Many homeowners reported water entering their properties, causing damage to ground-floor apartments, basements, and personal belongings. The flooding was particularly severe in the lower-lying neighborhoods, where the convergence of runoff from higher elevations intensified the flood impacts. This event highlighted the vulnerability of urban areas to intense rainfall, even when they don’t experience the most extreme precipitation in a regional storm. The combination of high-intensity rainfall, urban surfaces that prevent natural water absorption, and the concentration of people and property in a relatively small area created conditions for significant damage, despite the city receiving less rainfall than nearby rural areas.

The Statistical Puzzle

To understand the rarity of this event, we need to look at historical data. I analyzed the Annual Maximum Series (AMS) for 4-hour duration rainfall events from the Zichron Yaakov station (Table 1). This dataset spans from 1990 to 2022, capturing the highest 4-hour rainfall intensity for each year. The historical records show that the highest 4-hour rainfall intensity was 23.55 mm/hour in 2005-2006, followed by 15.20 mm/hour in 2021-2022, and 14.975 mm/hour in 2001-2002. The rest of the records range from about 14.9 to 4.2 mm/hour across different years.

When we look at the November 19, 2024 event, where Zichron Yaakov experienced an average intensity of 21.5 mm/hour over four hours (Figure 1), we can see that this ranks among the most intense storms in the station’s recorded history. This raises an important question: just how rare is an event of this magnitude?

*Table 1* :Historical Annual Maximum Series for 4-hour rainfall events at Zichron Yaakov station:

| Years | 4-hr Rain (mm/hr) |

|---|---|

| 2005-2006 | 23.550 |

| 2021-2022 | 15.200 |

| 2001-2002 | 14.975 |

| 2017-2018 | 14.925 |

| 2014-2015 | 13.825 |

| 2020-2021 | 12.050 |

| 1997-1998 | 11.975 |

| 1996-1997 | 11.825 |

| 2019-2020 | 11.725 |

| 1998-1999 | 11.425 |

| 2016-2017 | 11.075 |

| 1992-1993 | 10.938 |

| 2015-2016 | 9.325 |

| 2002-2003 | 9.225 |

| 2007-2008 | 9.200 |

| 2003-2004 | 9.025 |

| 2009-2010 | 8.600 |

| 2010-2011 | 8.275 |

| 2012-2013 | 8.000 |

| 2004-2005 | 7.400 |

| 1991-1992 | 7.250 |

| 1993-1994 | 6.875 |

| 2011-2012 | 6.450 |

| 2013-2014 | 6.375 |

| 2000-2001 | 6.225 |

| 2018-2019 | 6.200 |

| 2008-2009 | 5.850 |

| 1990-1991 | 5.813 |

| 2006-2007 | 5.500 |

| 1995-1996 | 4.188 |

Figure 1: Hyetograph analysis precipitation event that occurred in Zichron Yaakov, Israel.

To answer this question, I applied three different statistical distributions commonly used in hydrological analysis. Here’s where things get interesting. The Intensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) analysis used for developing new infrastructure design standards in the region suggested that a 4-hour rain event with intensities of 20-23mm/hour should have a probability of occurrence between 0.2% and 0.5% (Table 2) - in other words, a return period of 200-500 years.

Table 2 :The IDF analysis for shore line region of Israel for infrastructure design:

| Duration | 2 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | 20 Years | 25 Years | 50 Years | 100 Years | 200 Years | 500 Years | 1000 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 61 | 84 | 101 | 120 | 126 | 146 | 168 | 193 | 229 | 259 |

| 15 min | 49 | 68 | 83 | 99 | 104 | 122 | 141 | 162 | 193 | 219 |

| 20 min | 42 | 59 | 73 | 87 | 92 | 108 | 125 | 144 | 172 | 196 |

| 30 min | 33 | 47 | 57 | 69 | 72 | 85 | 98 | 113 | 135 | 153 |

| 45 min | 25 | 36 | 44 | 52 | 55 | 65 | 76 | 88 | 105 | 120 |

| 60 min | 20 | 28 | 34 | 41 | 43 | 51 | 60 | 69 | 83 | 96 |

| 90 min | 15 | 21 | 25 | 30 | 31 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 58 | 66 |

| 120 min | 12 | 17 | 20 | 24 | 25 | 29 | 34 | 39 | 46 | 52 |

| 180 min | 10 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 23 | 26 | 31 | 39 |

| 240 min | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 29 |

| 24 hr | 69 | 96 | 116 | 138 | 145 | 169 | 195 | 224 | 265 | 301 |

However, when we analyze the entire historical data from the Zichron Yaakov rain station using different statistical distributions, we get surprisingly different results:

Log-normal Distribution

- Probability Distribution Function:

where:

- μ = mean of the natural logarithm of the data

- σ = standard deviation of the natural logarithm of the data

- x = random variable (rainfall intensity)

| Duration | 2 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | 25 Years | 50 Years | 100 Years | 200 Years | 500 Years | 1000 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 60.4 | 75.4 | 84.6 | 95.7 | 103.6 | 111.3 | 118.8 | 128.6 | 136.0 |

| 20 min | 43.0 | 58.6 | 68.9 | 81.9 | 91.6 | 101.3 | 111.1 | 124.2 | 134.3 |

| 30 min | 34.1 | 47.7 | 56.9 | 68.0 | 77.4 | 86.3 | 95.3 | 107.5 | 117.0 |

| 40 min | 29.2 | 40.6 | 48.3 | 58.0 | 65.3 | 72.6 | 80.1 | 90.1 | 97.9 |

| 50 min | 26.0 | 35.9 | 42.4 | 50.7 | 57.0 | 63.2 | 69.5 | 78.0 | 84.0 |

| 1 hr | 23.1 | 32.1 | 38.1 | 45.7 | 51.4 | 57.2 | 63.0 | 70.9 | 77.0 |

| 1.5 hr | 17.5 | 24.6 | 29.3 | 35.4 | 40.4 | 46.4 | 49.3 | 55.7 | 60.6 |

| 2 hours | 14.5 | 20.3 | 24.2 | 29.2 | 33.0 | 36.8 | 40.7 | 45.9 | 50.0 |

| 2.5 hours | 12.5 | 17.6 | 21.1 | 25.3 | 28.8 | 32.2 | 35.6 | 40.2 | 43.8 |

| 3 hours | 11.2 | 15.9 | 19.1 | 23.0 | 26.3 | 29.5 | 32.7 | 37.1 | 40.5 |

| 3.5 hours | 9.9 | 13.9 | 16.7 | 20.2 | 22.8 | 25.5 | 28.2 | 31.8 | 34.7 |

| 4 hours | 9.1 | 12.5 | 14.8 | 17.7 | 19.9 | 22.1 | 24.3 | 27.3 | 29.6 |

| 4.5 hours | 8.4 | 11.5 | 13.5 | 16.0 | 17.9 | 21.1 | 21.7 | 24.3 | 26.3 |

| 5 hours | 7.8 | 10.6 | 12.5 | 14.9 | 16.8 | 18.4 | 20.0 | 22.6 | 24.5 |

| 6 hours | 6.8 | 9.3 | 10.9 | 13.0 | 14.5 | 16.0 | 17.6 | 19.7 | 21.2 |

Results: 21.5 mm/hours suggests a 2-1% probability (50-100 year return period)

Log-Pearson Type III Distribution

- Probability Distribution Function:

where:

- α = shape parameter

- β = scale parameter

- ξ = location parameter

- Γ(α) = gamma function

- x = random variable (rainfall intensity)

| Duration | 2 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | 25 Years | 50 Years | 100 Years | 200 Years | 500 Years | 1000 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.166 Hours | 60.55 | 75.41 | 84.47 | 95.26 | 102.89 | 110.25 | 117.41 | 126.67 | 133.57 |

| 0.333 Hours | 42.46 | 58.36 | 69.40 | 83.92 | 95.15 | 106.75 | 118.79 | 135.52 | 148.84 |

| 0.5 Hours | 33.65 | 47.50 | 57.37 | 70.61 | 81.05 | 91.96 | 103.45 | 119.63 | 132.70 |

| 0.66 Hours | 28.69 | 40.36 | 48.78 | 60.21 | 69.32 | 78.93 | 89.14 | 103.67 | 115.52 |

| 0.833 Hours | 25.58 | 35.66 | 42.83 | 52.48 | 60.10 | 68.08 | 76.51 | 88.40 | 98.03 |

| 1 Hours | 22.78 | 31.91 | 38.37 | 46.99 | 53.76 | 60.81 | 68.21 | 78.60 | 86.96 |

| 1.5 Hours | 17.21 | 24.41 | 29.61 | 36.67 | 42.29 | 48.23 | 54.53 | 63.49 | 70.80 |

| 2 Hours | 14.24 | 20.17 | 24.41 | 30.13 | 34.65 | 39.40 | 44.41 | 51.49 | 57.22 |

| 2.5 Hours | 12.45 | 17.60 | 21.17 | 25.87 | 29.49 | 33.23 | 37.09 | 42.44 | 46.68 |

| 3 Hours | 11.17 | 15.88 | 19.13 | 23.36 | 26.60 | 29.91 | 33.32 | 37.99 | 41.66 |

| 3.5 Hours | 9.84 | 13.92 | 16.75 | 20.47 | 23.35 | 26.31 | 29.37 | 33.62 | 36.99 |

| 4 Hours | 8.93 | 12.46 | 14.98 | 18.38 | 21.06 | 23.88 | 26.86 | 31.07 | 34.49 |

| 4.5 Hours | 8.22 | 11.37 | 13.66 | 16.80 | 19.32 | 22.00 | 24.86 | 28.96 | 32.34 |

| 5 Hours | 7.56 | 10.50 | 12.66 | 15.64 | 18.04 | 20.62 | 23.39 | 27.39 | 30.70 |

| 6 Hours | 6.65 | 9.20 | 11.05 | 13.60 | 15.64 | 17.82 | 20.15 | 23.50 | 26.25 |

Results: 21.5 mm/hours indicates a 2-1% probability (50-100 year return period)

Gumbel Distribution (Extreme Value Type I)

- Probability Distribution Function:

where:

- μ = location parameter

- β = scale parameter

- x = random variable (rainfall intensity)

| Duration | 2 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | 25 Years | 50 Years | 100 Years | 200 Years | 500 Years | 1000 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 59.8 | 74.1 | 83.6 | 95.6 | 104.5 | 113.4 | 122.2 | 133.8 | 142.6 |

| 20 min | 43.1 | 58.5 | 68.7 | 81.5 | 91.1 | 100.6 | 110.0 | 122.5 | 131.9 |

| 30 min | 34.4 | 47.8 | 56.7 | 67.9 | 76.2 | 84.5 | 92.7 | 103.5 | 111.7 |

| 40 min | 29.4 | 40.8 | 48.3 | 57.8 | 64.9 | 71.9 | 78.9 | 88.1 | 95.1 |

| 50 min | 26.1 | 35.9 | 42.4 | 50.6 | 56.7 | 62.7 | 68.7 | 76.6 | 82.1 |

| 1 hr | 23.2 | 32.1 | 37.9 | 45.3 | 50.7 | 56.2 | 61.6 | 68.7 | 74.1 |

| 1.5 hr | 17.7 | 24.7 | 29.3 | 35.1 | 39.4 | 43.7 | 48.0 | 53.7 | 57.9 |

| 2 hours | 14.6 | 20.4 | 24.2 | 29.0 | 32.6 | 36.2 | 39.7 | 44.4 | 48.0 |

| 2.5 hours | 12.7 | 17.7 | 21.0 | 25.0 | 28.3 | 31.4 | 34.4 | 38.5 | 41.0 |

| 3 hours | 11.3 | 16.0 | 19.0 | 22.2 | 25.8 | 29.1 | 31.5 | 35.3 | 38.1 |

| 3.5 hours | 10.0 | 14.1 | 16.8 | 20.0 | 22.7 | 25.2 | 27.7 | 31.0 | 33.3 |

| 4 hours | 9.1 | 12.7 | 15.0 | 18.0 | 20.2 | 22.4 | 24.6 | 27.5 | 29.6 |

| 4.5 hours | 8.4 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 16.4 | 18.4 | 20.4 | 22.3 | 24.9 | 26.9 |

| 5 hours | 7.8 | 10.8 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 18.8 | 20.8 | 23.2 | 25.2 |

| 6 hours | 6.8 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 13.2 | 14.8 | 16.4 | 18.0 | 20.1 | 21.7 |

Results: 21.5 mm/hours shows a 2-1% probability (50-100 year return period)

- the distribution analysis waas made on the entire data from the meterological station for a specific duration time series.

Why the Difference Matters

These varying results highlight a crucial point in hydrological analysis: the choice of statistical distribution can significantly impact our understanding of extreme events. While the IDF analysis suggests this is an extremely rare event, other statistical methods indicate it might be more frequent than we think.

Implications for Infrastructure Design

This discrepancy raises important questions for urban planners and engineers:

- Are we potentially underdesigning when we using a regional IDF’s?

- Or are we putting infrastructure at risk by using more less moderate statistical predictions?

- How do we account for climate change effects on rainfall patterns in our statistical analysis?

- Should we design infrastructure differently for urban areas versus less populated regions, given the different levels of potential impact?

Looking Forward

As our climate continues to change and extreme weather events become more frequent, the accuracy of our statistical models becomes increasingly important. This case study from the northern coastal region of Israel demonstrates that we need to be careful in how we interpret and apply rainfall statistics for infrastructure design, particularly in urban areas where the consequences of underestimating flood risks can be severe.

The varying results from different statistical distributions don’t necessarily mean that one approach is wrong and another right. Rather, they remind us that statistical analysis is a tool that requires careful consideration and perhaps a more comprehensive approach that considers multiple methods before making crucial infrastructure decisions.

This event serves as a valuable reminder that in hydrology, as in many fields of science, the story our data tells can vary significantly depending on how we choose to analyze it. As we face more extreme weather events, perhaps it’s time to reconsider how we approach rainfall frequency analysis and infrastructure design standards, especially in rapidly developing urban areas.